Dal verismo all'ultraromanticismo: "Cenere" di Grazia Deledda

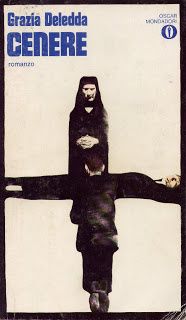

Cenere

di Grazia Deledda

Oscar Mondadori, Milano 1973

Grazia Deledda (1871-1936) compì solo studi elementari ma accumulò letture disparate che spaziano da Dumas a Balzac, da Scott alla Invernizio. Fu appassionata soprattutto di Eugene Sue che definì “atto a commuovere l’anima di una ardente fanciulla.” Come afferma Vittorio Spinazzola nella prefazione all’edizione Mondadori di “Cenere” del 73, la sua vocazione si alimenta di un “disordinato ultraromanticismo” incline all’enfasi e al melodramma.

“Leggeva di tutto, roba buona e roba mediocre, nella libreria messa insieme, un po’ a caso, dal padre; e obbediva all’istinto che le suggeriva di scrivere.” (Dino Provenzal)

I primi romanzi rientrano, infatti, nell’ambito di un gusto feuilletonistico. A disciplinare quest’apprendistato, fu decisivo l’influsso della narrativa verista. Ma trent’anni separano Giovanni Verga da questa verista in ritardo, che opera quando all’orizzonte si affacciano già d’Annunzio e Fogazzaro e subisce suo malgrado l’influsso di Flaubert, Zolà, Maupassant e del romanzo russo di Tolstoj e Dostoevskij.

Così ella si esprime a riguardo:

“Han detto che io imitavo in qualche modo il Verga, del quale conosco solo due o tre cose, tanto diverse dalle mie, e han tirato fuori autori tedeschi, francesi, inglesi, che io non conosco affatto. Dei russi non si parli! Io ho letto i romanzi russi solo dopo l’insistente paragone che i critici ne facevano.”

Mentre lentamente al verismo si sostituiscono correnti mistiche, simboliste e idealiste, e una più complessa ricerca psicologica dei personaggi romanzeschi, la Deledda ritrae caratteri, costumi e paesaggi della Sardegna con uno stile che oscilla fra realismo e fiaba. Le sue pagine rivelano una visione del destino umano legato a forze misteriose e il regionalismo dei suoi scritti è visto in un alone favoloso, superstizioso, di vita rurale e primitiva. Il Sapegno fa notare la mancanza d’ideologia a favore di “un’aura commossa e incantata”.

Afferma Dino Provenzal: “Per quanto, a proposito di un’artista indipendente, originale come la Deledda mi ripugni citare uno schema, credo che la formula bontempelliana “realismno magico” non potrebbe avere un’attuazione migliore.”

Anche se meno famoso degli altri romanzi, proprio “Cenere”, del 1904, fu citato nella motivazione del premio Nobel che la Deledda ricevette nel 1926. Come negli altri romanzi, il tema è quello consueto della scrittrice, l’incapacità di opporsi alla forza delle passioni, in special modo quelle amorose, da parte di noi creature, “fragili come canne”, tutt’altro che superuomini dannunziani, ma anzi, pervasi dall’orrore e dal peccato. La scrittrice, tuttavia, non analizza il turbamento dei personaggi ma si limita a riviverne l’emotività.

Insorge prepotente nei protagonisti la coscienza del peccato, unita a un’inquietudine e a una spiritualità religiosa estranea al verismo che è, soprattutto, vergine e barbarica, panteista e animista. Così, se la corte dei miracoli dei personaggi nuoresi ha tratti victorughiani, - e, guarda caso, è proprio una copia de “I miserabili” che lo studente Anania tiene aperta sul tavolo della camera -

“vibrava nel silenzio caldo il silenzio acuto di Rebecca, che saliva, si spandeva, si spezzava, ricominciava, slanciavasi in alto, sprofondavasi sotterra, e per così dire pareva trafiggesse il silenzio con un getto di frecce sibilanti. In quel lamento era tutto il dolore, il male, la miseria, l’abbandono, lo spasimo non ascoltato del luogo e delle persone; era la voce stessa delle cose, il lamento delle pietre che cadevano ad una dai muri neri delle casette preistoriche, dei tetti che si sfasciavano, delle scalette esterne, e dei poggiuoli di legno tarlato che minacciavano rovina, delle euforbie che crescevano nelle straducole rocciose, delle gramigne che coprivano i muri, della gente che non mangiava, delle donne che non avevano vesti, degli uomini che si ubriacavano per stordirsi e che bastonavano le donne ed i fanciulli e le bestie perché non potevano percuotere il destino, delle malattie non curate, della miseria accettata incoscientemente come la vita stessa.” pag. 66

- Olì, la ragazza madre poi donna perduta, ci ricorda la figlia di Iorio.

Il vitalismo naturale dei personaggi porta alla loro sofferenza, ai tormenti della coscienza e alla perdizione, il tabù fa più paura proprio a chi è fatalmente destinato a infrangerlo, e un amore proibito porta sventura. Tuttavia, i protagonisti non hanno intima cognizione del male, non vi si abbandonano perciò completamente, rimangono innocenti, come innocente, lirica, pura, e al contempo spietata, indifferente, è la natura.

“In mezzo ai campi quell’anno coltivati dal mugnaio, sorgevano due pini alti, sonori come due torrenti. Era un paesaggio dolce e melanconico, qua e là sparso di vigne solitarie, senza alberi, né macchie. La voce umana vi si perdeva senza eco, quasi attratta e ingoiata dall’unico mormorio dei pini, le cui immense chiome pareva sovrastassero le montagne grigie e paonazze dell’orizzonte.” pag.59

Proprio la natura accompagna tutti gli stati d’animo, li sottolinea, se ne fa correlativo oggettivo, alter ego.

Anche se il personaggio principale è il giovane Anania, la madre, Olì, rimane protagonista assoluta, giganteggia sullo sfondo, con la sua assenza che si fa presenza ingombrante e destino segnato, con l’infamia del suo lavoro, con l’umiliazione dell’abbandono, con l’odio amore che ella suscita nel figlio. Vittorio Spinazzola definisce “Cenere” “una sorta di Bildungsroman incentrato su un complesso edipico”.

La nostalgia per il ritorno alle origini nasconde il desiderio del recupero della comunione biologica con la madre e la pulsione amorosa viene sublimata nell’espiazione della morte, eterno connubio di eros e thanatos.

--------

Grazia Deledda (1871-1936) did not study but accumulated disparate readings ranging from Dumas to Balzac, from Scott to Invernizio. She was especially passionate about Eugene Sue who defined "fit to move the soul of an ardent girl." As Vittorio Spinazzola states in the preface to the Mondadori edition of "Cenere" in 73, his vocation feeds on a "disordered ultra-romanticism" prone to emphasis and melodrama.

"She read about everything, good stuff and mediocre stuff, in the library put together a little randomly, by her father; and obeyed the instinct that suggested that she wrote. " (Dino Provenzal)

The first novels fall, in fact, in the context of a feuilletonistic taste. To this apprenticeship, the influence of the realistic narrative was decisive. But thirty years separate Giovanni Verga from this late verista, who works when D'Annunzio and Fogazzaro already appear on the horizon and in spite of herself is influenced by Flaubert, Zolà, Maupassant and the Russian novel by Tolstoy and Dostoevsky.

So she says about it:

“They said that I somehow imitated the Verga, of whom I know only two or three things, so different from mine, and they brought out German, French, English authors, whom I don't know at all. Don't talk about Russians! I only read Russian novels after the persistent comparison that critics made of them. "

While slowly substituting mystical, symbolist and idealistic currents to realism, and a more complex psychological research of romance characters, Deledda portrays characters, customs and landscapes of Sardinia with a style that oscillates between realism and fairy tale. Her pages reveal a vision of human destiny linked to mysterious forces and the regionalism of her writings is seen in a fabulous, superstitious halo of rural and primitive life. Sapegno points out the lack of ideology in favor of "a moving and enchanted aura".

Dino Provenzal states: "Although, as far as an independent, original artist like Deledda is concerned, I cite a scheme, I believe that the Bontempellian formula" magical realism "could not have a better implementation."

Although less famous than the other novels, "Cenere", from 1904, was mentioned in the motivation of the Nobel Prize that Deledda received in 1926. As in the other novels, the theme is that of the writer, the inability to oppose the force of passions, especially those of love, by us creatures, "fragile as reeds", anything but D'Annunzio supermen, but rather, pervaded by horror and sin. The writer, however, does not analyze the disturbance of the characters but merely relives their emotionality.

The conscience of sin arises overbearingly in the protagonists, combined with a restlessness and a religious spirituality extraneous to realism which is, above all, virgin and barbaric, pantheist and animist. So, if the court of miracles of the Nuoro characters has Victorian traits, - and, coincidentally, it is a copy of "Les Miserables" that the student Ananias keeps open on the bedroom table -

“Rebecca's high-pitched silence vibrated in the warm silence, rising, spreading, breaking, starting again, rushing up, sinking underground, and so to speak seemed to pierce the silence with a jet of hissing arrows. In that lament was all the pain, the evil, the misery, the abandonment, the unheard spasm of the place and the people; it was the voice of things, the lament of the stones falling one by one from the black walls of the prehistoric houses, of the roofs that fell apart, of the external stairs, and of the worm-eaten wooden balconies that threatened ruin, of the euphorbias that grew in the rocky streets, of the couch grass that covered the walls, of the people who did not eat, of the women who did not have clothes, of the men who got drunk to knock themselves out and who beat the women and the children and the beasts because they could not beat destiny, of the untreated diseases, misery as unconsciously accepted as life itself. "

- Olì, the mother girl and then the lost woman, reminds us of Iorio's daughter.

The natural vitalism of the characters leads to their suffering, to the torments of conscience and to perdition, the taboo scares more precisely those who are destined to break it, and a forbidden love brings misfortune. However, the protagonists have no intimate knowledge of evil, they do not completely abandon themselves to it, they remain innocent, as innocent, lyrical, pure, and at the same time ruthless, indifferent, is nature.

"In the middle of the fields cultivated by the miller that year, there were two tall pines, sounding like two streams. It was a sweet and melancholy landscape, scattered here and there with solitary vineyards, without trees or woods. The human voice was lost without echo, almost attracted and swallowed by the only murmur of the pines, whose immense foliage seemed to dominate the gray and red mountains of the horizon. "

Nature itself accompanies all moods, underlines them, makes them objective correlative, alter ego.

Although the main character is the young Ananias, the mother, Olì, remains the absolute protagonist, looms in the background, with her absence becoming a cumbersome presence and marked destiny, with the infamy of her work, with the humiliation of abandonment, with the hatred love that she arouses in her son. Vittorio Spinazzola defines "Cenere" as "a sort of Bildungsroman centered on an Oedipus complex".

Nostalgia for the return to origins hides the desire for the recovery of biological communion with the mother and the love drive is sublimated in the atonement of death, the eternal union of eros and thanatos.

/image%2F0394939%2F20190531%2Fob_6113d1_61425960-10216728261030327-19684367693.jpg)

/image%2F0394939%2F20240406%2Fob_c8e51a_71jtg77well-ac-uf1000-1000-ql80.jpg)

/image%2F0394939%2F20240401%2Fob_7cac52_una-favolosa-eredita-00-1.jpg)

/image%2F0394939%2F20240328%2Fob_4b28b2_doc-nelle-tue-mani.png)

/image%2F0394939%2F20240121%2Fob_309338_lost-in-space-serie.jpg)